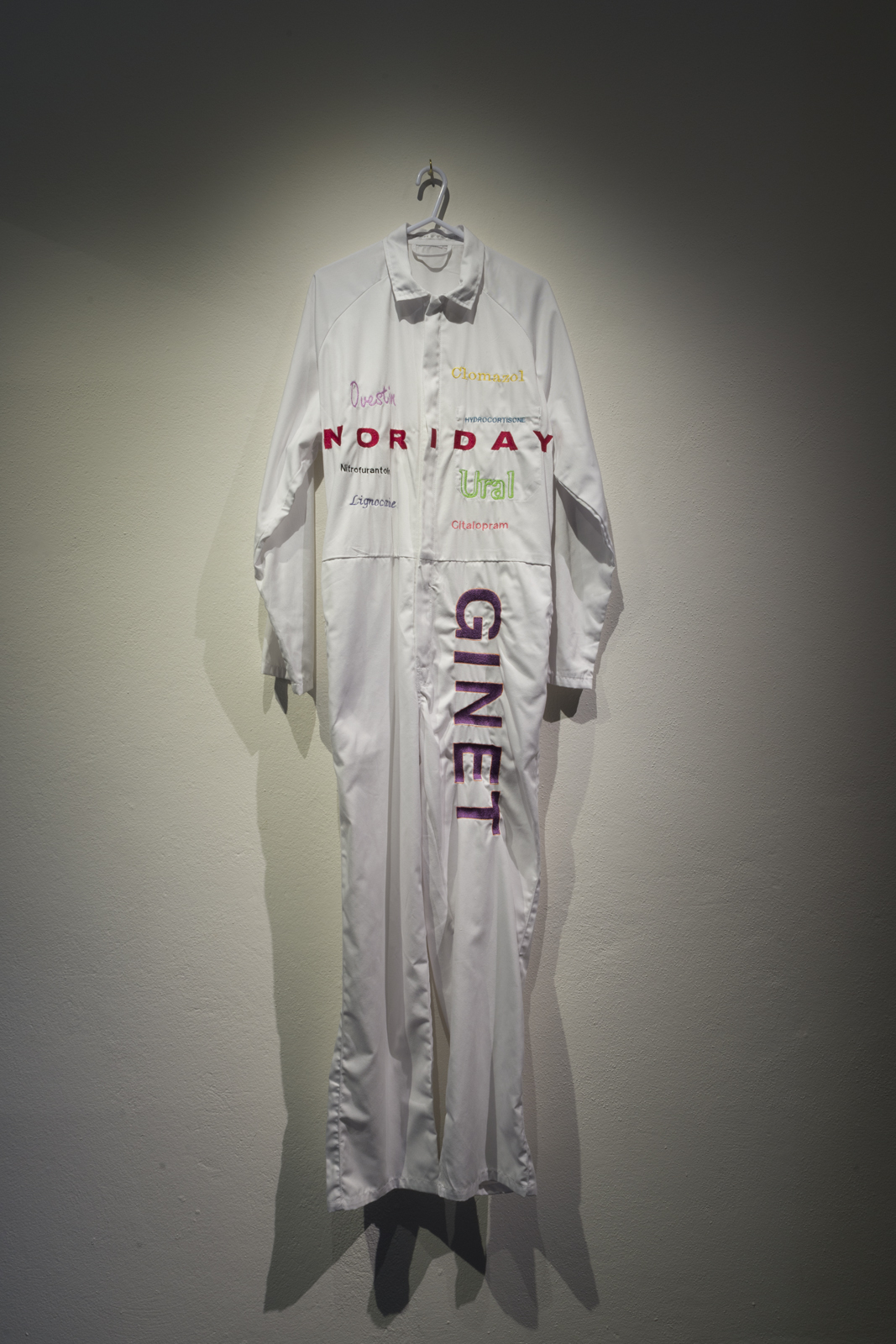

Box, Box, Box

2017

Embroidered Worksuit

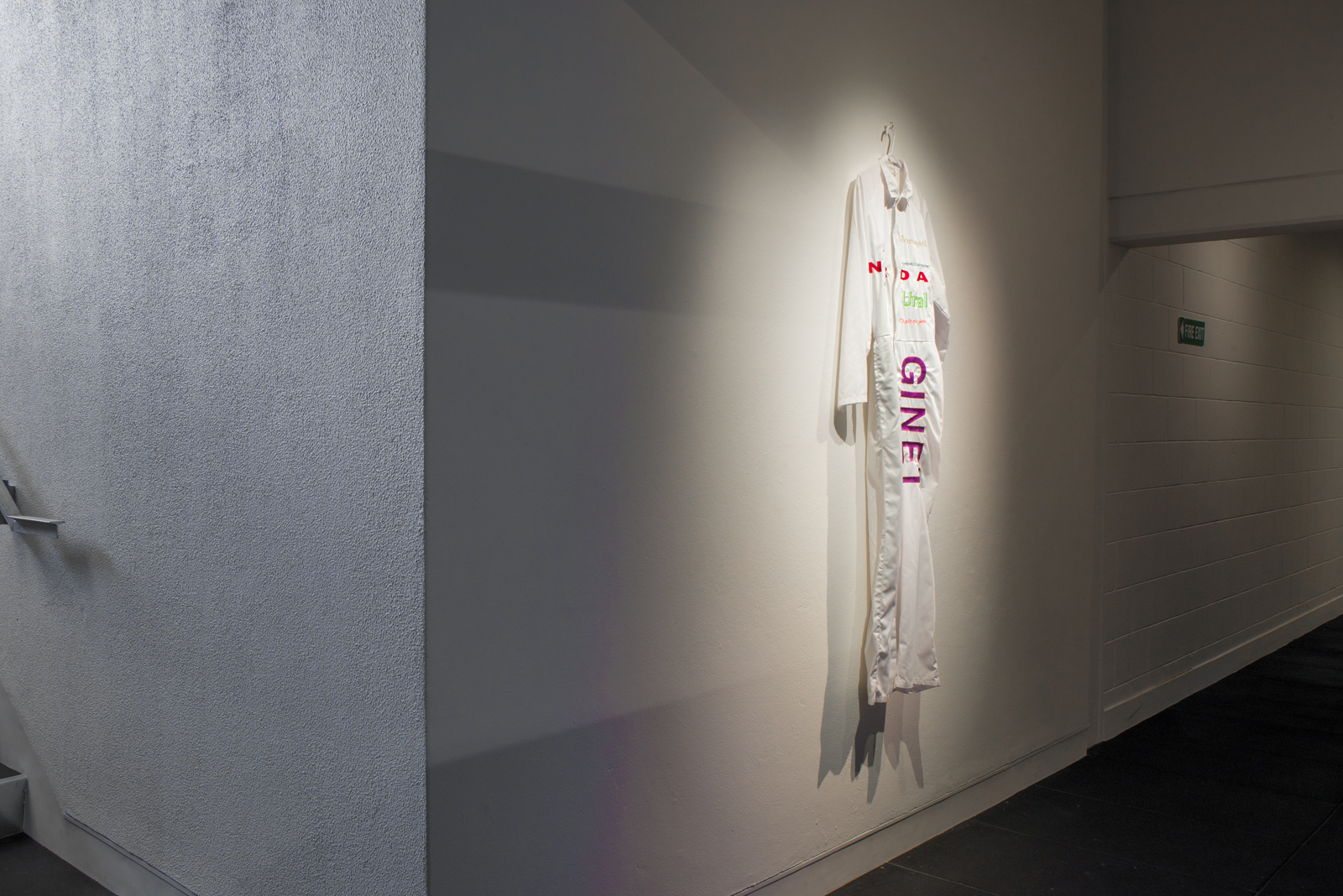

The Adam Art Gallery as part of The Tomorrow People

*sold

Text by Ellie Lee-Duncan (EL-D) for The Tomorrow People publication

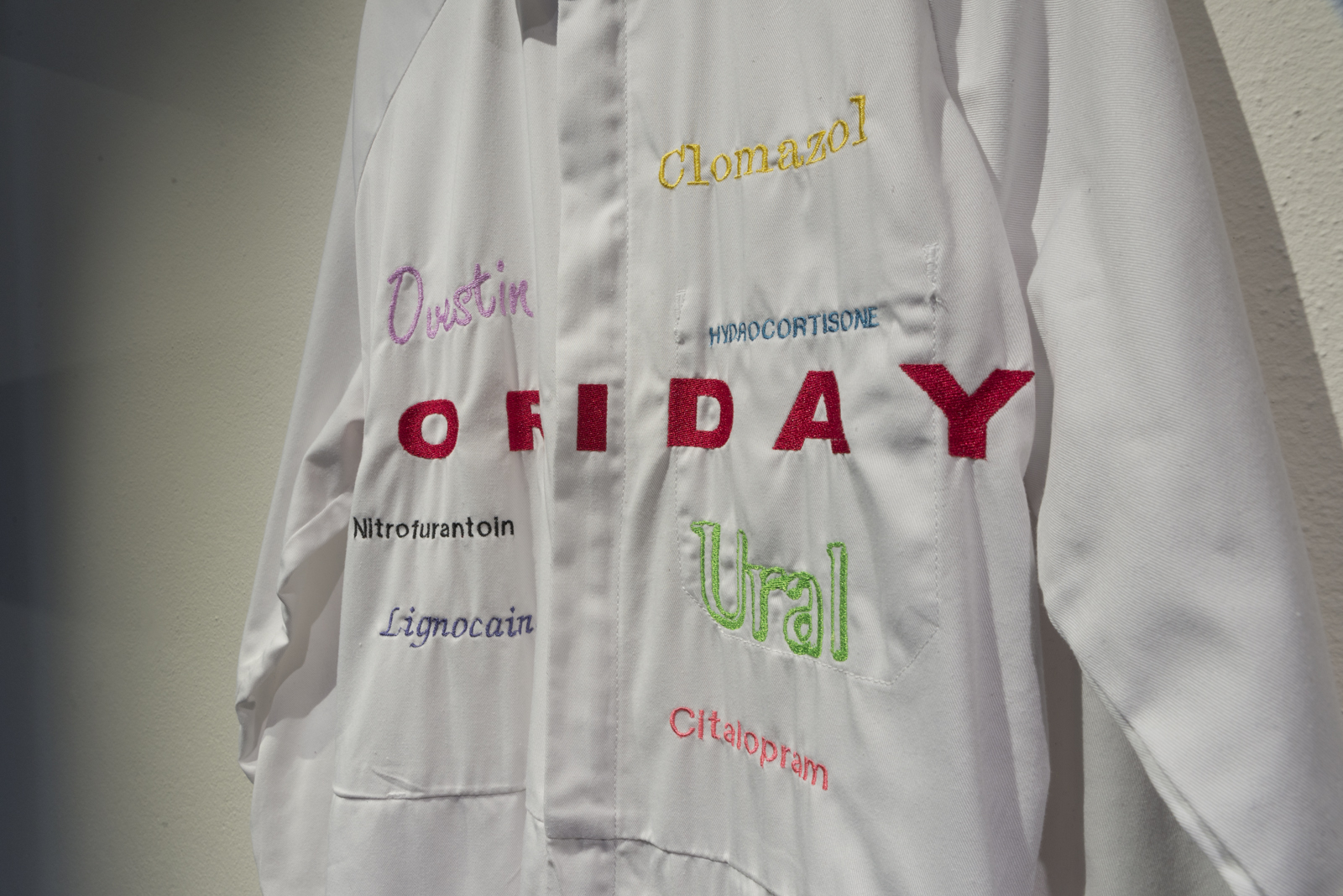

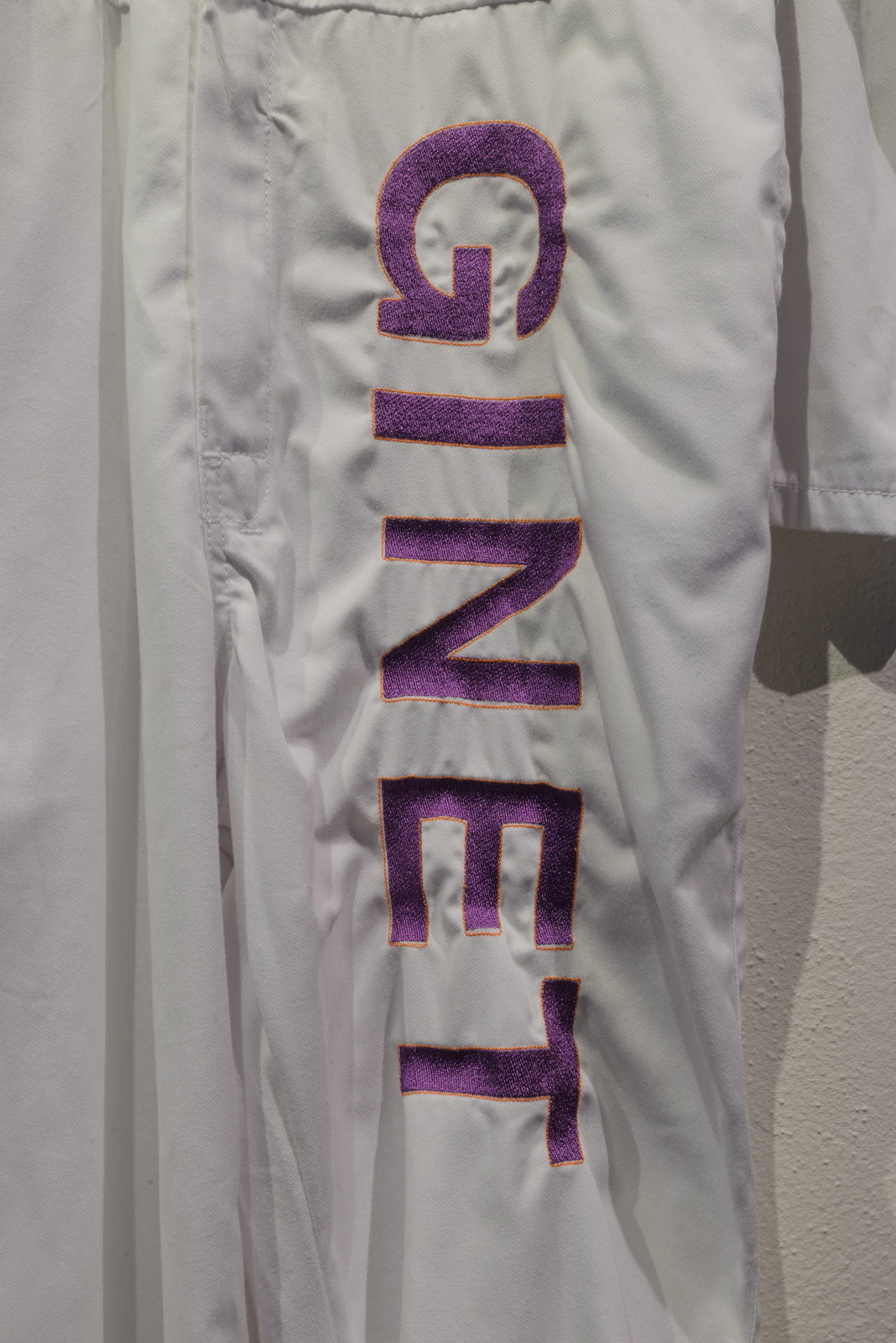

A white jumpsuit is embroidered with the names and logos of various medications and medical creams, covering the suit-like racing emblems. The crisp, sterile material implies medical treatment, yet it is not a hospital gown. Instead, the jumpsuit has a hidden fastening down the front, and emphasizes a specific removal of access to the body: it reads ‘impenetrable’. Embroidery is traditionally thought of as women’s art, suited to those with limited social mobility. Within a patriarchal hierarchy, it is perceived as a lesser decorative art opposed to the ‘fine’ arts. Despite countless feminist artists who have used embroidery as an act of defiance and reclamation, it is still often denied access within the art gallery. By choosing these logos and projecting them onto an ‘other’ external body-like form, Maddy enables an externalised evaluation of their purpose and practical value. Placing what has been prescribed for her onto something outside of herself, she elects to contemplate these medicines on her own terms. Although Maddy removes herself physically from the work, the jumpsuit stands in for her body, the legs and sleeves softly hanging.

For over a year and a half, she has sought medical treatment for an as-of-yet-undiagnosed medical condition. Refusing to provide her with the necessary referral to a gynaecologist for specialist treatment, a string of doctors has instead elected to prescribe Maddy medication to treat her symptoms, rather than diagnosing or treating the underlying condition. Each medication stitched here has been prescribed; the crowded logos dot the unseen body, medicalisation envisioned at the expense of individual autonomy and identity. Gatekeeping systematically limits public access to healthcare services in order to reduce demand and cost. A referral from a primary-source healthcare provider is necessary, negating individual autonomy and a authority of knowing oneself. Untreated and undiagnosed gynaecological problems are common; not only because of lack of access to appropriate services and the reluctance to deal with unwanted physical contact during examinations, but also due to the underlying physical symptoms being routinely dismissed as a psychological problem. Relegating painful and uncomfortable symptoms to the status of mere ‘symptom moving the priority from essential medical diagnostics and treatment to an individual’s responsibility for their own mental health. One logo, Ovestin, displays gendered marketing techniques in pretty, pink cursive script. Although Maddy never asked for it or used it, a doctor prescribed this numbing vaginal lubricant. Encouraged to use it so she was able to have sexual intercourse, it was given on the basis of a particularly heteronormative assumption that she needed it, prioritising a male partner’s pleasure at the expense of her own comfort. Possessing ‘female’ anatomy, yet not all its functions; her doctors’ prescriptions seem driven by a desire to construct a semblance of biological heteronormative usage, seeking to solve her ‘female’ dysfunctionality rather than finding the cause of the pain.